Left in the Dark: How Ghana’s Informal Workers Are Overlooked in the Green Energy Surge

- Winston Tackie

- Sep 29, 2025

- 4 min read

Ghana is positioning itself as a regional leader in the race to decarbonize, with a policy architecture and investment appetite that promise cleaner power and a greener economy. Ambitious targets set out in the Ghana National Energy Transition Framework (2022–2070) aim to reduce fossil fuel dependence and expand renewable capacity. These commitments align with the Paris Agreement and with Sustainable Development Goal 7 on affordable, reliable and modern energy. Yet as solar farms rise and investors align portfolios with Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) standards, a persistent omission threatens the fairness and durability of Ghana’s progress. The informal workforce, whose livelihoods and everyday contributions are too often invisible to mainstream ESG frameworks, risks being left behind.

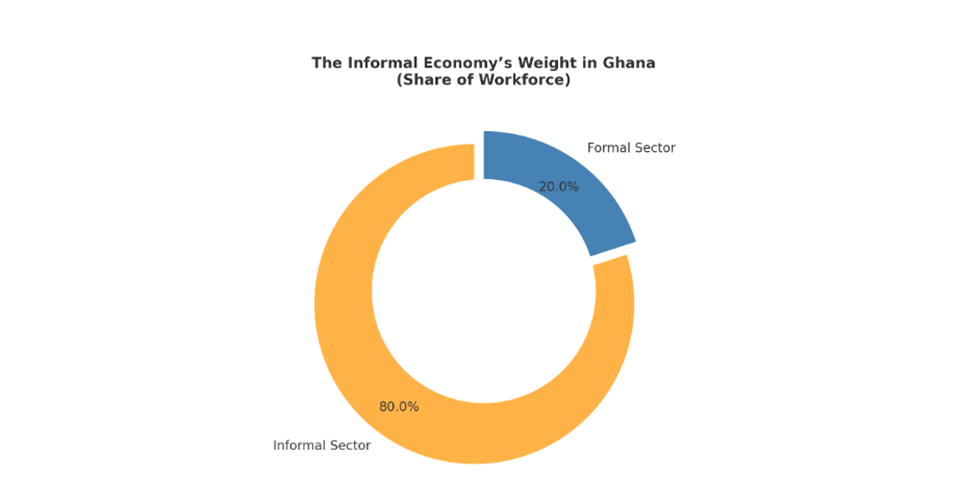

The informal economy in Ghana is vast and varied, encompassing market traders, transport operators, small-scale miners, waste collectors, artisans and countless micro-entrepreneurs who keep towns and cities functioning.

More than four out of every five Ghanaians work in the informal economy.

Source: Ghana Statistical Service, 2022.

According to the Ghana Statistical Service, more than 80 percent of the country’s workforce is employed informally. These workers operate without formal contracts, social protections or consistent access to public services, and they therefore shoulder policy shocks disproportionately. Green regulations that are well-intentioned, such as restrictions on diesel vehicles, the introduction of electric vehicle mandates without supportive infrastructure or bans on harmful artisanal mining practices, can carry heavy livelihood costs when implementation ignores the realities on the ground. Without deliberate mitigation, the energy transition risks becoming a source of displacement rather than opportunity.

A closer look at local realities exposes how policy can unintentionally marginalize those who are already vulnerable. In Greater Accra, thousands of motorcycle taxi operators commonly called “okada” riders provide essential last-mile mobility in neighborhoods underserved by formal transit. Policies that curtail “okada” operations for safety or emissions reasons, combined with volatile fuel prices, have left many riders grappling with shrinking incomes and no transitional assistance. In municipal waste systems, informal collectors and scavengers perform the labour of recycling and recovery that formal contractors profit from.

Yet when municipalities introduce stricter collection standards or require certified equipment, informal actors are expected to comply without access to capital or integration into formal value chains. In mining districts, small-scale miners confront enforcement actions and outright bans meant to curb environmental damage. Without viable alternative livelihoods or retraining programs, these measures can devastate household incomes and inflame social tensions, as highlighted in earlier studies on Ghana’s mining economy (Osei-Boateng and Ampratwum, 2011).

These examples reveal an ESG blind spot rooted in three avoidable shortcomings. Social safeguards are frequently insufficient or absent, and there is little in many ESG frameworks that guarantees minimum health and safety standards, income protection or social insurance for informal workers affected by green policies. The voices of the informal sector are rarely heard in the design and rollout of transition measures, and policy decisions that affect daily survival are too often made in meeting rooms where market actors and technocrats outnumber the people who will be most affected. Impact measurement also remains inadequate, with a dearth of reliable data on how green regulations alter informal livelihoods. Global analyses by the International Labour Organization show that informal workers face some of the highest risks of exclusion in sustainability transitions, yet national ESG reporting rarely captures these vulnerabilities.

Reframing ESG to be genuinely inclusive will require practical and targeted action. Investors and regulators should require that major green projects and policy reforms include social impact assessments focused explicitly on informal workers and their communities. Such assessments must be followed by tangible mitigation measures, including targeted subsidies for fuel or tools where appropriate, conditional cash transfers or micro-insurance products to cushion income shocks, and grant or loan facilities to help informal cooperatives invest in cleaner technologies. Participatory policy processes are equally essential.

Establishing formal channels for representation, whether through associations of market traders, waste picker cooperatives or transport unions, will surface pragmatic solutions and reduce resistance. Blended finance structures that combine public climate funds, donor grants and concessional lending, as promoted by the African Development Bank, can underpin micro-grants, training programs and cooperative financing. These approaches would provide pathways for informal workers to transition into greener and more stable livelihoods.

These proposals are realistic but not easy. Ghana’s tight fiscal space constrains the scale of subsidies and social programmes that the state can fund unilaterally, and there will inevitably be resistance from formal sector incumbents who see the formalisation of informal actors as competitive pressure. Monitoring and enforcement in informal contexts are inherently complex because of mobile workforces, fragmented networks and limited recordkeeping. Nonetheless, the cost of exclusion is higher. Policies that marginalize large swathes of the workforce risk economic dislocation, erode public trust and could provoke social unrest.

Such outcomes would undermine both development goals and investor confidence. Moreover, international investors and ESG auditors are increasingly attuned to social justice metrics. Failure to demonstrate inclusive transition plans could translate into reputational risk and reduced access to finance, a point emphasized in World Bank assessments of Ghana’s economic resilience.

Ghana’s experience carries lessons for other low and middle-income countries undertaking green transitions. The informal sector is not a niche concern but the backbone of many developing economies. A sustainable energy transition that leaves informal workers behind will breed inequality and fragility while undermining the moral and practical case for green growth. Conversely, designing policies that integrate social protection, voice and finance into the environmental agenda can produce a model of transition that is resilient, equitable and replicable across the continent.

If Ghana is to realise its ambitions, policymakers, financiers, civil society and community representatives must treat inclusivity not as an optional add-on but as a central pillar of energy strategy. Informal workers are not peripheral actors but essential participants in the nation’s economic fabric. When transition planning places their livelihoods and perspectives at the center, Ghana can demonstrate that environmental progress and social justice are mutually reinforcing. In doing so, the country can set a standard for just transitions globally.

Comments